Explore which countries have the shortest average work weeks in 2025, what drives their reduced hours, and the lessons other nations can learn. Data-rich, visually engaging, with global comparisons and best practices.

When individuals discuss the countries with the shortest workweeks, they are seldom describing the same thing. Some refer to the legal maximum working hours, while others speak of the official "full-time" status, and many refer to the typical number of hours worked in reality. For this piece, we emphasize the last of these — the average actual weekly hours measured in labor surveys and monitored by organizations such as the International Labour Organization (ILO) and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

That figure represents a fact. It includes full-time and part-time workers, accounts for unpaid overtime when it occurs, and shows how many hours the typical person is working in the labor market. It matters because the amount of time people spend working determines not just the economy, but also health outcomes, family formation, and even national cultures.

A shorter work week is also associated with decreased stress, less burnout, and greater life satisfaction. Meanwhile, shorter hours don't necessarily equal less output. Some of the globe's most productive per-hour economies — the Netherlands and Germany, for example — also have some of the most abbreviated work weeks. That seeming contradiction has made the topic particularly pertinent in 2025, as governments and businesses try out four-day weeks, hybrid schedules, and new approaches to work-life balance.

This article takes a close look at which countries currently enjoy the shortest workweeks, what explains their success, what the benefits and challenges look like, and what lessons others might borrow.

Across the world, working time varies dramatically. Some nations are still wrestling with average weeks of 48 to 50 hours or more, while others consistently report under 30 hours on average. The gap reveals not just economic development, but also cultural values and policy choices.

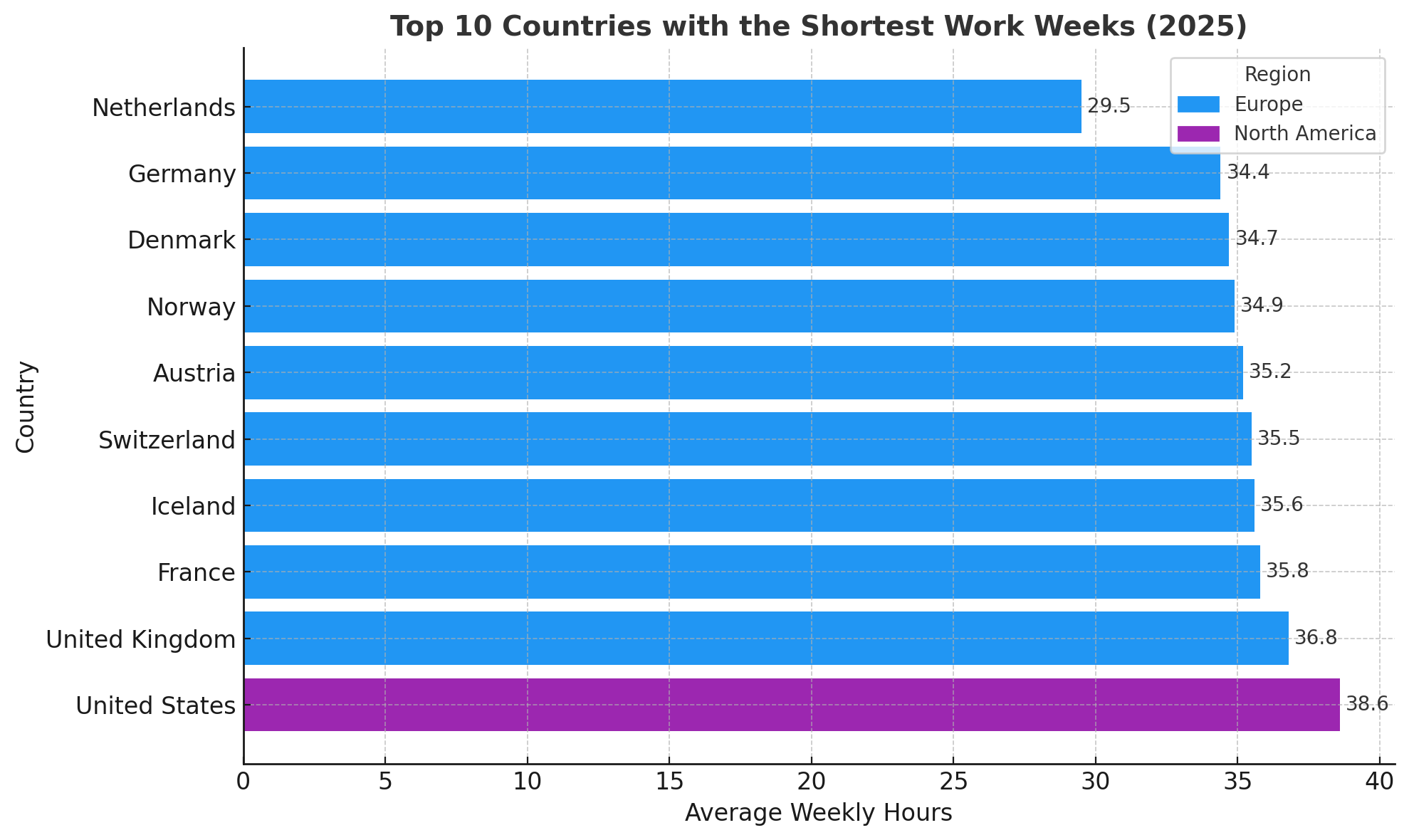

Here are some of the countries that consistently appear at the top of the rankings for shortest work weeks in 2025:

1. Netherlands — around 29.5 hours per week

Among developed economies, the Netherlands is the poster child for reduced work weeks. Almost half of all Dutch workers are employed part-time, and most do so by choice, not because they need to. Parents tend to adjust their schedules in order to be with children, and the culture does not frown upon working fewer hours. High productivity per hour keeps the economy competitive even with a lower average week.

2. Germany — around 34.4 hours per week

Germany combines one of the world’s most productive labor forces with robust worker protections and collective bargaining rights. The result is an economy that thrives on efficiency rather than long hours. German employees enjoy generous vacation time and relatively short average weeks, yet continue to produce high-value industrial exports.

3. Denmark — around 34.7 hours per week

In Denmark, the cultural expectation is work-life balance. Short working weeks are enabled by robust welfare systems, parental leave entitlements, and leisure-oriented workforces. The Danish labor market is fluid, and part-time working is an honored choice in many sectors.

4. Norway — around 34.9 hours per week

High pay and oil wealth allow Norway to maintain shorter working weeks without sacrificing living standards. Unionization rates are high, and collective bargaining shields workers from being pushed into excessive working hours..

5. Austria — around 35.2 hours per week

Austria balances its industrial production with a rich tradition of appreciating leisure and family time. Like Europe's neighbors, it enjoys EU labor protections and robust unions that keep hours in line.

6. Switzerland — around 35.5 hours per week

Known for its productivity and wealth, Switzerland proves that shortened work weeks and efficiency are not necessarily mutually exclusive. Employees are paid high wages and enjoy companies that focus on streamlined operations that cut wasted time.

7. Iceland — around 35.6 hours per week

Iceland has come under attention for national experiments with shorter working hours. Thousands of workers participated in pilots that reduced hours but not pay. The results showed consistent productivity and improved well-being, prompting broader take-up.

8. France — around 35.8 hours per week

France's 35-hour work week, legalized in 2000, still influences culture in the workplace despite exceeding it daily for many employees through overtime. Working hours per week remain below international averages, making France one of those countries where shorter weeks are part of national identity.

9. United Kingdom (36.8 hrs/week)

The UK averages just under 37 hours per week. While full-time jobs remain common, the rise of remote work, flexible schedules, and part-time employment post-pandemic has shifted national averages downward. Ongoing debate around a four-day week has further put the UK in the spotlight, with trials showing positive effects on both productivity and employee well-being.

10. United States (38.6 hrs/week)

The U.S. sits higher than Europe but lower than Asia’s long-work cultures. The widespread comes from a mix of gig economy roles, part-time jobs, and full-time overwork in professional sectors. Healthcare tied to employment often incentivizes longer hours, but flexibility in remote jobs and a growing four-day work week movement are slowly reshaping norms.

Work patterns are not evenly distributed across the globe. When you look at the data region by region, a story emerges about history, culture, and economic structure.

1. Europe

Europe consistently reports the world’s shortest workweeks. Nations like the Netherlands (29.5), Germany (34.4), and Denmark (34.7) are below the global average. Why?

There is generous paid holiday time and widely prevalent part-time arrangements. All this makes a labor market in which working less is both legally secured and socially accepted.

2. Oceania

In Australia and New Zealand, weeks hover near 38–40 hours (OECD average). But in Pacific islands like Vanuatu (24.7) and Kiribati (27.3), the numbers are far lower. Why?

These countries have substantial informal and subsistence economies. Fishing, farming, and household-based activities offer a livelihood without requiring lengthy wage labor hours. In that context, "short work weeks" don't always signify the same degree of comfort as in the North of Europe, but they still denote a style of life with greater time outside formal work.

3. Asia

Asia has nearly the reverse story. Some of its economic giants — South Korea, Japan, Singapore — have among the longest working weeks in the advanced world, frequently 45 to 50 hours or more.

Yet, reforms are emerging:

4. North America

North America is in between. Canada and the United States work about 36 to 39 hours weekly, not far behind Europe, though the U.S. tends to have more variation because of part-time and gig work.

Mexico is among the world's longest-working nations, with means in excess of 48 hours. The contrast in North America itself — between Mexico and its neighbors to the north — illustrates how cultural and economic influences define hours as much as geography.

5. Africa and Latin America

Africa and Latin America are both extremely diverse. In some of Africa, particularly the poorer economies, long working hours are the rule because salaries are low and, in order to make a living, people need to have several jobs at once.

In Latin America, Mexico and Colombia frequently lead the "longest hours" league, with levels significantly above 45 hours per week. But there are also other countries in the region, such as Chile or Argentina, that are near the world average and occasionally try out labor reforms.

The nations that manage to keep the average work week short have a number of common attributes. These combine synergistically to account for the way individuals can work shorter hours but remain economically strong.

1. Strong labor regulation and collective bargaining

Legal frameworks set the foundation. The European Union’s Working Time Directive caps the maximum work week at 48 hours, but in practice, many countries legislate or negotiate much lower.

Germany, for example, has collective industry bargains that limit hours and require generous overtime pay, so employers are cautious about pushing employees to unreasonable levels. Unions are important because they bargain for equilibrium instead of just greater pay.

Here is why?

2. High productivity per hour worked

Behind shorter work weeks is a simple math problem: the more value you generate per hour, the less time you must work to maintain income. Northern Europe is the most productive in the world, through modern industries, solid education systems, and technology investments. The manufacturing industry of Germany and the services industry of the Netherlands are evidence that efficiency can replace time worked.

3. Cultural acceptance of part-time and flexible work

Norms are important. In certain nations, a 60-hour week is an honor badge; in others, it is an indication that something has gone badly wrong. The Netherlands is such an exception: practically half the workforce is part-time, and parents often shift their schedules to mind the kids.

In contrast to the United States, where part-time employment is frequently associated with precarious work arrangements, Dutch part-time employees are strongly protected and their benefits prorated. That cultural tolerance lowers the national average. Social safety nets and welfare systems

4. Social safety nets and welfare systems

When the state provides healthcare, schooling, and pensions, employees do not need to work second jobs just to meet basic needs. That is an important distinction between Europe and countries with less robust safety nets.

In America, for example, individuals can work extended hours to have access to employer-sponsored health care, while in Norway or Denmark, this system is not based on work.

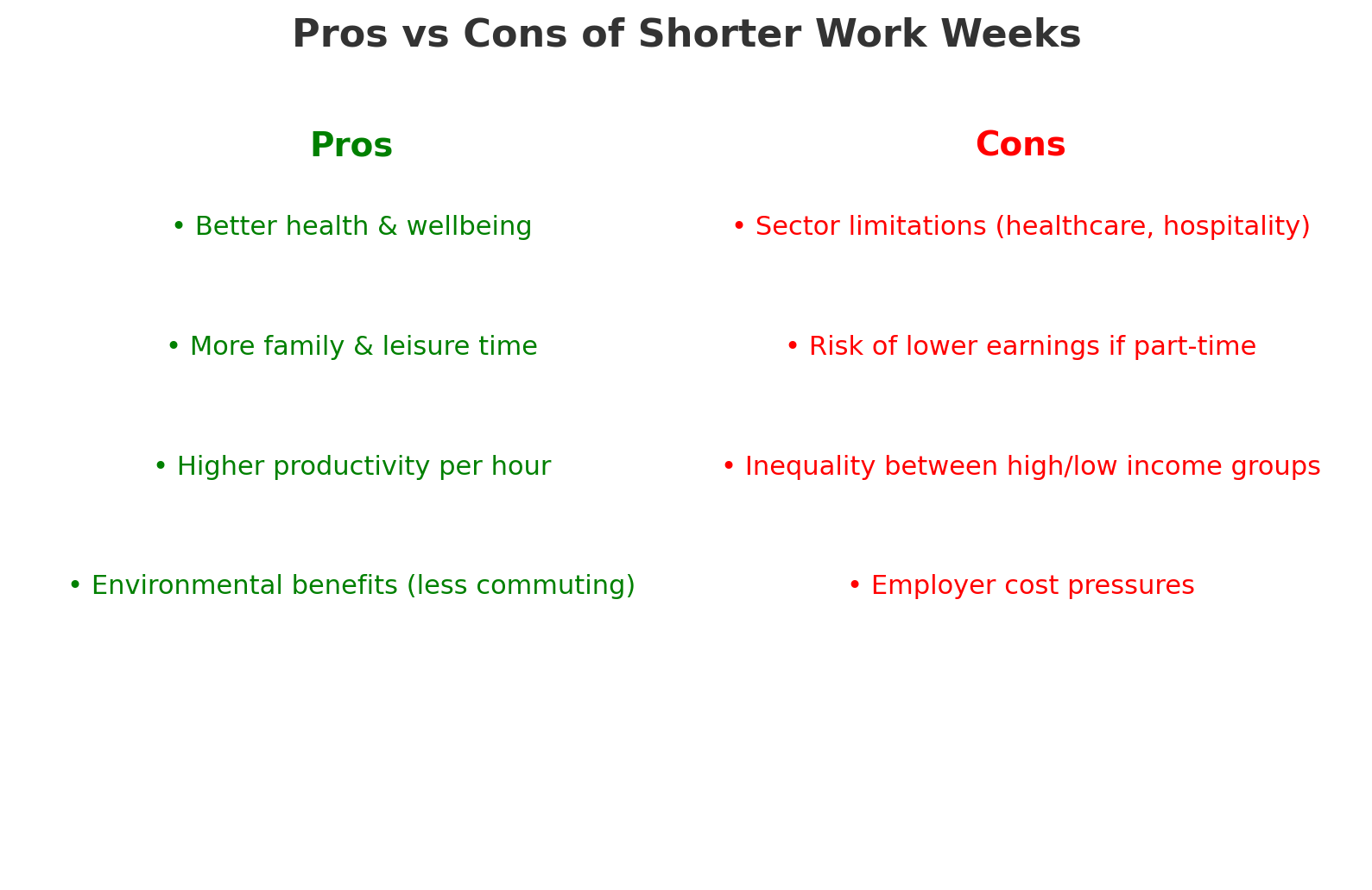

For workers, the appeal of shorter work weeks is obvious. But like any major shift in economic life, the picture is not entirely one-sided. Both benefits and trade-offs deserve attention.

The benefits

The trade-offs

Shortened weeks are not issue-free. Certain industries simply cannot condense hours without increasing personnel.

The balance, therefore, is sophisticated. Shorter workweeks are genuinely promising but no panacea. They are best implemented with the help of productivity growth, laws that safeguard against exploitation, and policies that avoid making inequality surge.

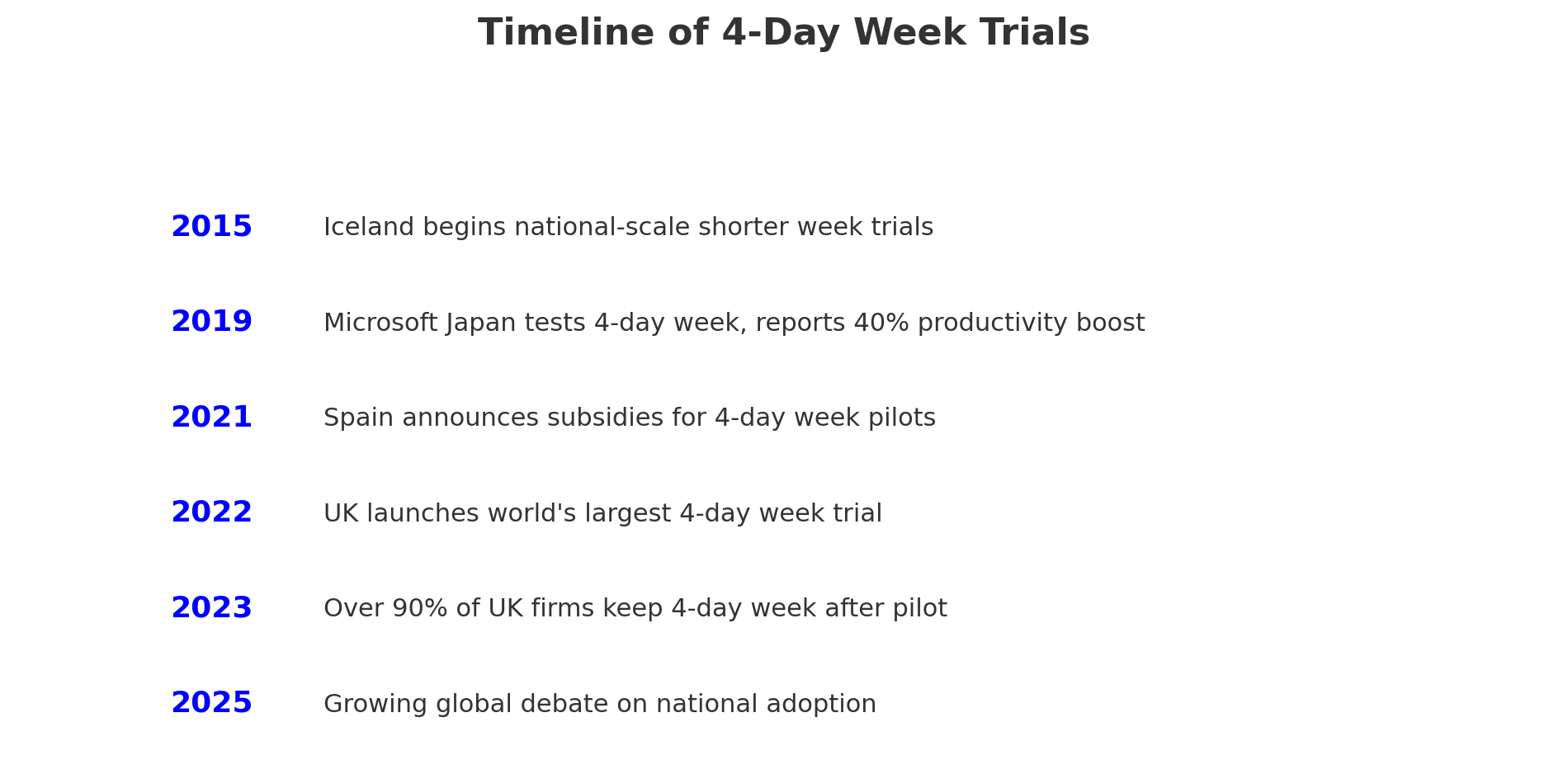

The idea of shorter work weeks is no longer just a theoretical debate. Over the past decade, dozens of trials have tested what happens when people work less, and the results have been closely watched around the world.

1. Iceland’s pioneering trials

Iceland, between 2015 and 2019, ran one of the world's most ambitious experiments, impacting more than 2,500 public sector workers, school staff, and office workers. Workers cut their working time from 40 to 35 or 36 hours without sacrificing pay.

The results were dramatic: productivity was stable or improved, and employees felt healthier, less stressed, and more content. The experiments were considered a resounding success, and Icelandic workplaces have widely adopted shorter hours ever since.

2. The UK’s four-day week experiment

Between 2022 and 2023, over 60 British companies took part in the world's largest simultaneous four-day work week experiment. Employees kept 100 percent of their salaries while their working hours were reduced to approximately 32 per week.

It was reported that firms held their level of production, lowered turnover, and found that absenteeism decreased.

Staff widely supported the initiative, and the majority of the trial-participating businesses decided to extend the policy after it had concluded.

3. Spain’s government-funded pilot

Spain has also adopted a more structured policy response, providing subsidies to medium and small-sized businesses willing to try shorter workweeks.

By allowing businesses to cover the costs of transition, the government aims to show that shorter hours can be a feature of long-term labor reform.

Initial findings indicate that productivity can be kept flat, but sectoral realities are evident — manufacturing, for example, involves more complicated scheduling transitions than office-based services.

4. Experiments in Asia

Even where long hours are the norm, change is on the horizon. Japan has been urging employers to provide voluntary four-day workweeks in an effort to enhance family life and stem falling birth rates.

Some big companies, such as Microsoft Japan, saw a sharp boost in productivity in a month-long test when workers worked four days a week rather than five.

The takeaway from these pilots is consistent: when reductions are well-designed, productivity does not collapse. In many cases, it improves.

Workers report higher well-being, employers see stronger retention, and societies benefit from healthier, more engaged citizens. The challenge lies in scaling these experiments from select workplaces to entire economies.

For nations or employers considering a move toward shorter work weeks, the experiences of early adopters provide a roadmap. The following lessons stand out:

For policymakers, these recommendations can be packaged into a practical toolkit: pilot, protect, invest, support, customize, and communicate. Each element builds the conditions for shorter work weeks to succeed without undermining economic stability.

The 20th century was defined by the 40-hour work week. The 21st century may redefine that norm downward.

Ultimately, the debate is not just about economics. It is about values. Do societies prioritize endless work, or do they balance labor with time for health, family, and creativity? As automation and technology reshape the future of jobs, this question becomes more pressing.

If the last century was about proving that workers should not labor six days a week, this one may be about proving that less can truly be more — more health, more happiness, and even more productivity.